SLOW MADE in Indonesia…

With over 17,000 tropical islands to call home, Indonesia is a cultural fascination. From batik to betel nuts and every island culture in between, this region has some of the world's poorest places but is so rich with island life traditions.

Since launching in 1998, THREADS OF LIFE have been working directly with more than 35 artisan groups on islands from Kalimantan to Timor, to help empower communities and preserve ancient cultures, unique to this great archipelago’s humble existence.

THOUSANDS OF ISLANDS WOVEN IN TIME

SLOW MADE THREADS OF LIFE with artisan partners | DESTINATION INDONESIA

INTERVIEW WITH William Ingram with Jean Howe (FOUNDERS) | photography kindly contributed by Jean Howe

Founders Jean Howe and William Ingram. Photo by Teman Kerja.

AS THE LARGEST ARCHIPELAGO IN THE WORLD, INDONESIA IS A MAGNIFICENT SPRINKLE OF MORE THAN 17,000 TROPICAL ISLANDS! (APPROX. 6,000 ARE INHABITED.) THREADS OF LIFE PLAYS AN INTEGRAL ROLE TO HELP PRESERVE SO MANY UNIQUE COMMUNITIES AND ANCIENT CULTURES ONLY FOUND IN THIS REGION. SINCE LAUNCHING IN 1998, HOW IS EVERYTHING PROGRESSING?

When we started, our focus on high-quality, natural-dyed textiles strongly differentiated us from both the global market and the communities where textiles were made. In the villages, trends moved away from what was being portrayed as old fashioned. Recent years have seen a resurgence of local cultural pride and the wearing of traditional cloth, with the wealthy and high-ranking officials seeking to distinguish themselves by wearing natural-dyed work. The best dyers and weavers can do well selling their work, but it is at the edges of the traditions that weavers are falling away and taking up other means of income. The risk is that the overall tradition erodes over time.

HOW DID ‘THREADS OF LIFE’ BEGIN?

My wife Jean and I moved to Bali in 1993, to further our personal interests in Indonesia’s diverse traditional cultures by leading tours of Bali and the Nusa Tenggara islands of southeast Indonesia. During the Asian Economic Crisis of 1998 and one of the severest El Nino-induced droughts in living memory, we saw people in the communities we were visiting with no money or food, only their heirlooms to sell.

To help address this economic and cultural crisis, Threads of Life was born. Starting with a dozen weavers in the village of Lamalera on the island of Lembata we began commissioning and buying textiles from the communities we had already formed relationships with when operating the tours. For the first three years we sold at trunk shows in America, before opening a signature store in Bali in 2001.

WHERE DID YOU GROW UP AND WHERE DO YOU LIVE NOW, AND WHY?

I grew up very comfortably in the UK, but as a young adult I felt very uneasy with the life path ahead of me. I could see how consumerism was destroying the natural world and wanted something different. I went to Japan and then onto Bali, and it was here that I found a worldview offering some answers to my questions. Not with the Hinduism here, per se, more in the underlying culture which I found to be archipelago-wide, the more I started to travel in this region. Learning from this culture still fascinates me thirty years on.

PLEASE SHARE A LITTLE ABOUT YOUR OWN PASSIONS AND PURSUITS, TO HELP RESTORE TRADITIONAL CULTURES AND CRAFTSMANSHIP IN INDONESIA?

When travelling across eastern Indonesia, the material culture you see is either traditional architecture or traditional cloth. The cloth is a much more accessible art and learning about it offered me a window into a way of life so different from my own. The focus on natural dyes created a connection to the landscape and I learnt both the dye methods and where the plants used were grown. My passion is really to learn. It would be arrogant of me to say I’m here to save these cultures. The people will save their own cultures if they want to. But I will do what I can do to help those with a passion for maintaining the traditions from which I am learning so much.

WHERE IS THREADS OF LIFE BASED AND HOW HAVE THE ARTISAN CONNECTIONS BEEN ESTABLISHED AND MAINTAINED WITH THESE REMOTE ISLAND COMMUNITIES OVER THE YEARS?

We are based in Bali for several reasons. For Jean and I, it is where we want to live. As a tourist destination, it is the market for indigenous textiles that makes the Threads of Life business work. As an organisation doing lots of field work with indigenous, animistic communities the culture of our Balinese field staff allows them to meet the communities we visit as peers with a shared world view, and this has been of enormous benefit in our work with traditional weavers.

OF THE THOUSANDS OF ISLANDS HOW MANY ISLANDS HAS THREADS OF LIFE HAD ACCESS TO AND HOW MANY ISLAND COMMUNITIES ARE INVOLVED IN THIS COLLABORATIVE PROGRAM?

We work with over 1,000 women weavers in 50 communities on 12 islands. There are many more places we would like to work but as a small organisation in such a large archipelago we are only able to do so much.

TEXTILES AND WEAVING ARE THE MOST PROMINENT TRADITIONAL CRAFTS FOUND IN THIS REGION, YET EACH ISLAND SEEMS TO HAVE A UNIQUE STYLE AND DESIGN, WHICH IS FASCINATING AND PROVES HOW PRECIOUS AND EXQUISITE CULTURAL TRADITIONS ARE TO PRESERVE. HOW DO YOU THINK THE WORLD CAN COLLECTIVELY HELP TRADITIONAL CULTURES AND COMMUNITIES SURVIVE INTO THE FUTURE?

We can help artisans sustain livelihoods by buying their work. But to do this in a sensitive way we need to understand their craft and techniques to support the highly-skilled and tradtional craftsmanship over low-quality or mass-produced replicas. Learning how to differentiate between these levels is difficult, so finding an authoritative and responsible supplier or agent is very important. To support cultures and their world views we also need to recognise that our buying power is a force, both good and bad.

These cultures are being eroded by consumerism and yet it is our consumer spending that supports artisans and their traditional livelihoods. It's a contradiction really, but the balance of impacts can be tipped more in their favour so that their world view is as equally valued as ours. We can learn from their perspective to help guide fair trade consumerism.

ANOTHER CULTURAL FASCINATION FOR VISITORS IS THE BETEL NUT. THEY’RE A LOCAL STAPLE THROUGHOUT INDONESIA, AS WELL AS A GENEROUS CEREMONIAL OFFERING FOR GUESTS. IN FACT, THERE ARE MANY VARIATIONS OF TRADITIONAL BETEL NUT CARRY POUCHES OR BAGS MADE ON THE INHABITED ISLANDS. CAN YOU SHARE A LITTLE ABOUT THE HISTORY OF THE BETEL NUT? WHERE ARE THEY GROWN AND SOURCED FOR DAILY CONSUMPTION?

The betel nut quid is a combination of three ingredients. There is either the leaf or inflorescence of the Piper betel plant, which gives the ‘betel’ to the quid’s name. The ‘nut’ is from the Areca catechu palm. Both the ‘betel’ and the ‘nut’ are grown all across the archipelago. The chemistry of the quid is activated by a little slaked lime, made from limestone or mollusk shells that are burned and then doused with water. Sharing the makings of the quid is the core of good social etiquette: guests bring leaves and nuts, and hosts offer leaves, nuts and lime. Bringing and offering the quid makings in a stylish container is both respectful to the receiver and a source of pride for the giver.

“Be humble. Be respectful. visit to learn. See everyone as your equal. Seek to build relationships. We have seen tourists come into a village and just wander through people’s homes, taking pictures and posing themselves wherever they want, as if the village is a museum and the people are of no consequence. This is an extreme example but industrialised culture tends to express this hubris, unless we consciously check our cultural habits."

William Ingram (Founder, Threads of life)

Flores Island:

Seneng baskets (pictured) hold the ingredients of the betel nut quid. Locals always carry betel nuts to offer their hosts, assuring a kind reception wherever they travel to other villages. The Seneng basket belongs specifically to a female traveller. This seneng basket (pictured) has been hand-woven by master artisan Feliksia Kiren (pictured with Seneng). Her floral, geometric design is rare, difficult and demonstrates Feliksia's high level of skill and craftsmanship.

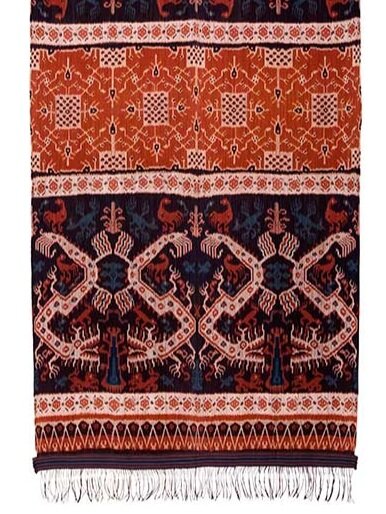

Sumba Island:

The hinggi (pictured) is hand-woven as two pieces and joined with an almost invisible seam. The hinggi is worn in identical pairs by the Sumbanese man, folded over the shoulder and wrapped around the hips. Individual designs and motifs express qualities associated with augmenting the wearer’s personal power during life and aiding his journey to the next world after death. Motifs are usually arranged in three to five bands of varying width. Traditionally, the design announced a man’s social status.

The kalumbut hada (pictured) is a beaded betel nut bag worn by the male papanggangu - a ritual representative at important ceremonies.

Betel Nuts:

Pinang or betel nuts from the palm tree, Areca catechu (pictured right) are chewed from Africa to Oceania. It is said the betel nut opens the way to honest and friendly conversation. Chewing betel also suppresses appetites… a useful side-effect in regions where food and water are not plentiful. A quid of pinang, with the leaves and peppery flower spikes from the malesireh plant (Piper betle), combined with powdered lime produce a mild intoxication… and those friendly, red-saliva smiles.

SEAFARING BETWEEN ISLANDS IS TRADITIONALLY NOT SO COMMON. OR IS IT NOW? HOW DO YOU BELIEVE THESE MICRO-CULTURES HAVE SURVIVED AND CONTINUED TO SUSTAIN THEMSELVES IN ISOLATION? THERE MUST BE SOME INVALUABLE WISDOMS TO LEARN FROM THESE INGENIOUS ISLAND COMMUNITIES?

There has always been travel and trade between these islands. Motifs can be found on traditional textiles that show influence of trade from India, China and beyond, going back two millennia. Cloves that were found only in the Moluccan Islands were traded as far as Egypt over 3500 years ago. This was not an isolated corner of the human world but an integral part of it. And yet, people were not reliant on trade for survival. Complex cultures arose in response to the opportunities and limitations of each island’s environmental conditions and the ways in which people had to interact with the more-than-human world in order to live sustainably.

IT MUST BE A VERY REWARDING EXPERIENCE TO BE WORKING IN THIS REGION, HELPING TO RESTORE TRADITIONAL CULTURES. WHAT IS THE MOST IMPORTANT THING A TRAVELLER CAN DO TO HELP SUPPORT LOCAL COMMUNITIES ON VISITING THE ISLANDS?

Be humble. Be respectful. Come to learn. See everyone as your equal. Seek to build relationships. We have seen tourists come into a village and just wander through people’s homes, taking pictures and posing themselves wherever they want, as if the village is a museum and the people are of no consequence. This is an extreme example but industrialised culture tends to express this hubris, unless we consciously check our cultural habits.

WHICH ISLAND COMMUNITIES WOULD YOU RECOMMEND TO VISIT FOR AN AUTHENTIC SLOW TRAVEL EXPERIENCE? WHAT HAS BEEN A FAVOURITE ISLAND TRAVEL MEMORY FOR YOU?

Flores is a great destination. From Komodo National Park in the west to Larantuka in the east, you can take weeks visiting villages, meeting weavers, seeing indigenous architecture. There will be well-documented places to visit everywhere. Use these lists as a start point. See which direction most people are going, then turn ninety degrees and start walking.

SHIBUI & Co. would like to thank Threads of Life and their artisan partners for sharing their beautiful story with us.